Part One: Why does Indiana educate incarcerated individuals?

A five-part article series exploring corrections education in Indiana

By Anna Kezar

Of the 25,000 individuals incarcerated in Indiana, 90% will reenter society, according to the Indiana Department of Corrections.

What sort of people will these individuals be when they return? The outcome is most influenced by what was achieved during their time in prison.

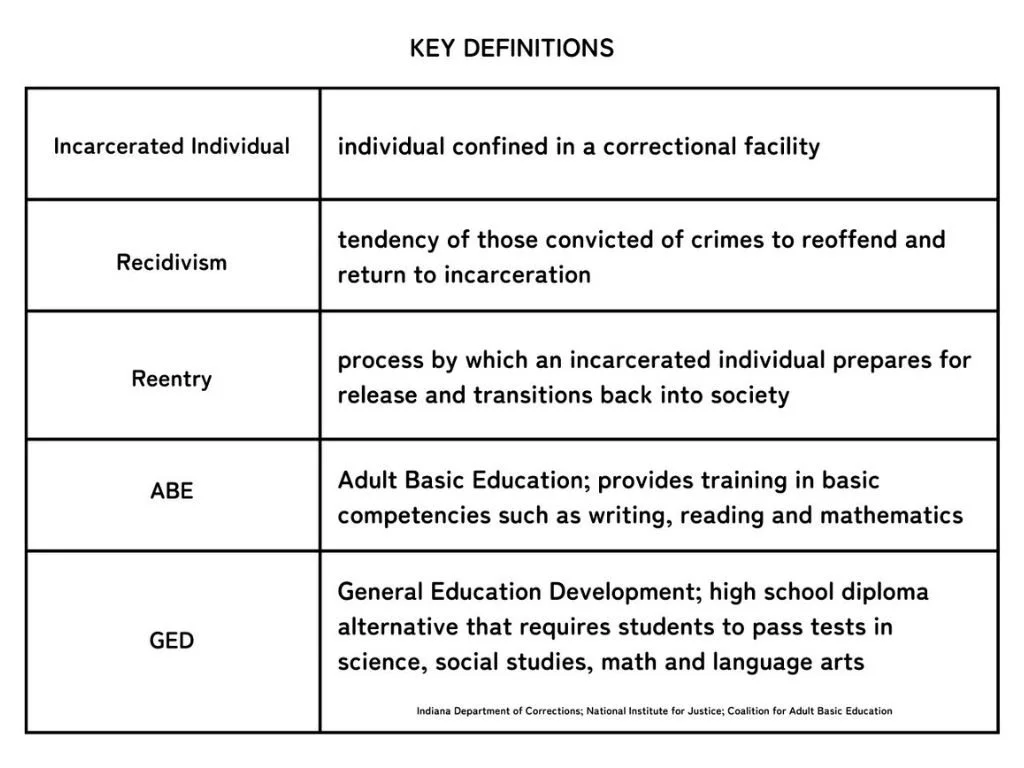

For many years the value of education has been determined by how it helps to reduce recidivism – the tendency of incarcerated individuals to return to incarceration after release. In Indiana, recidivism is defined as the reincarceration of an individual within three years of their release date.

Indiana’s recidivism rate is 34%, as compared to the national average of 68%, according to a 2023 report by the IDOC. Individuals who participate in correctional education programs are 28% less likely to recidivate than those not participating in correctional education programs, as reported in a 2018 meta-analysis by the Journal of Experimental Criminology.

“They’re going to be our neighbors. They’re going to live next to us, they’re going to work next to us,” Patrick Callahan, director of adult education and training for the IDOC, said. “There’s a whole host of reasons to do this. We all want good neighbors and this [education] gives us an opportunity to improve on that.”

Education reduces recidivism for a variety of reasons, according to the Journal of Correctional Education. It provides incarcerated individuals with structure and discipline and gives them something to look forward to. It increases self-esteem and confidence in intellectual abilities, which decreases violent tendencies. Education gives opportunities to exercise critical thinking and moral reasoning skills.

Education also supplies interaction with those outside of the facility through communication with teachers and staff contracted by educational institutions. Interactions with those dedicated to their success offer hope for incarcerated individuals to see a future for themselves beyond prison.

“We can disagree about a lot of things when it comes to incarceration, but you cannot disagree with the notion that if we just warehouse people we aren’t doing any good,” Callahan said.

If incarcerated individuals are released with the same level of job skills they came in with, it shouldn’t be a shock when they are reincarcerated, according to Callahan.

Education is not only about reducing recidivism, but developing skills that will provide better employment. Those who cannot get a job after reentry are 60% more likely to recidivate, as reported by the IDOC. Those who receive education in prison have 13% higher odds of obtaining employment post-release, according to the 2018 meta-analysis by the Journal of Experimental Criminology.

“We don’t want to just have them not come back to prison,” Danielle Cox, corrections education chair for the Coalition for Adult Basic Education, said. “I want to make sure they don’t come back to prison because they have a job with a liveable wage.”

Job acquisition, retention and advancement are all crucial to reducing recidivism. Higher level of education received correlates to a higher level of income. Wage earnings increase by $9,000 annually with high school completion, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The higher level of income, the less likely the behaviors that caused incarceration will be repeated.

On a national scale, for every 400,000 people who earn their high school diploma, the tax base increases by $2.5 billion, according to a 2022 report by the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy.

“Certainly, when you put those dollars on the front end to improve somebody’s life, you save money on the back end,” Callahan said.

Education helps incarcerated individuals reenter society sooner. As outlined in the Indiana Corrections Code 37-50-6-3.3, time credits can be earned based on participation in the individual’s case plan. This plan could include participation in a substance abuse program, life skills training, education or other programs. Time credits ranging from six months to two years can be applied based on the type and level of education received.

“If we don’t do anything then we have only ourselves to blame,” Callahan said. “Something works somewhere, doing nothing works nowhere.”

Education Options

Nationally, there are four education options for an incarcerated individual: Adult Basic Education, General Education Development, vocational certificates and post-secondary degrees.

ABE provides training for adult learners focused on basic competencies – literacy, including reading and writing, and mathematics. Students test at the completion of each level and receive certificates for each one achieved.

ABE is offered in all Indiana state prisons. The majority of incarcerated individuals test at a low to intermediate level, although the younger the individual, usually the higher their level due to having more recently received secondary education, according to Danielle Cox, corrections education chair for the Coalition for Adult Basic Education.

After completing ABE, students can work toward a GED, a high school equivalency diploma. It requires students to pass tests in science, social studies, mathematical reasoning and reasoning through language arts. All Indiana state prisons offer GED preparation and testing.

Upon GED completion, students may enroll in a vocational training program or post-secondary education.

Vocational certifications include programs such as coding, welding, culinary arts, building trades, business technology and cosmetology. A student receives a certificate upon completion of a certain number of hours and passing required tests.

The programs are often designed to provide training for high-demand fields. Because of this, incarcerated individuals who complete vocational programs have a high likelihood of job placement. Construction trade programs are among the most successful in the nation in terms of employment. Vocational programs are offered at 13 Indiana state prisons.

College programs represent the least implemented education opportunity for incarcerated individuals in the U.S. as 35% of state prisons offer access to college-level courses. In Indiana, four out of the 18 state correctional facilities provide post-secondary education.

The recidivism rate drops to 8% for incarcerated individuals who earn a bachelor’s degree. Cox explains that receiving a GED alone is no longer enough for incarcerated individuals to obtain job security post-release.

“You’ve got to make sure before they’re released they have something other than just their GED,” Cox said.

Many incarcerated individuals who receive post-secondary degrees get jobs within the human services sector upon release. These individuals can use their past experiences to support others going through similar experiences by being peer recovery specialists or addiction counselors, thus impacting the programs that helped them.